Shaped by time, our ports reflect our industrial and economic history.

Taking an interest in their spatial organization means looking at the different policies that have underpinned our foreign trade.

Looking at them may also be a way of imagining what will happen next, after the great transition we are going through.

What follows is a short, illustrated look at our country’s recent port, industrial and economic history.

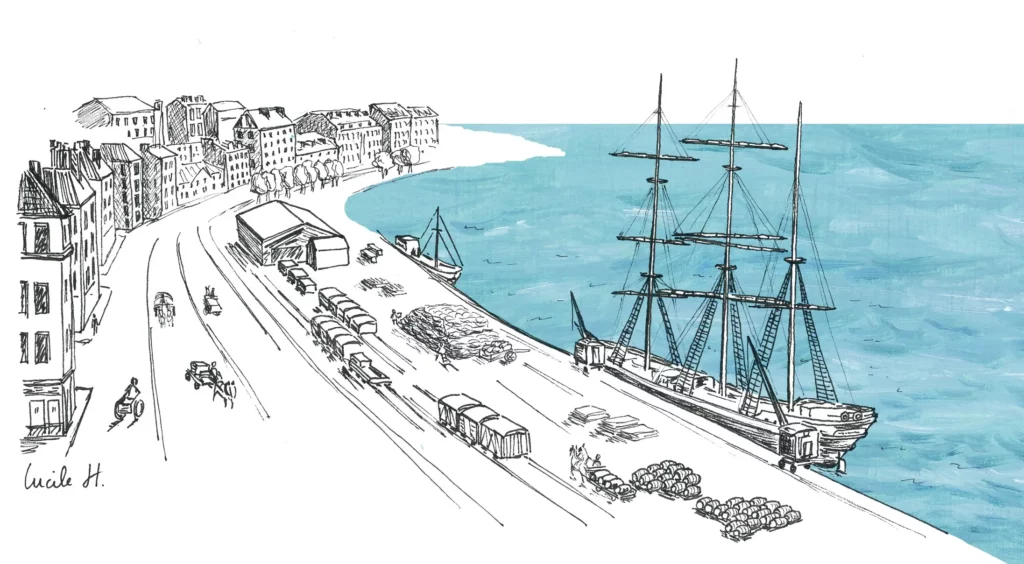

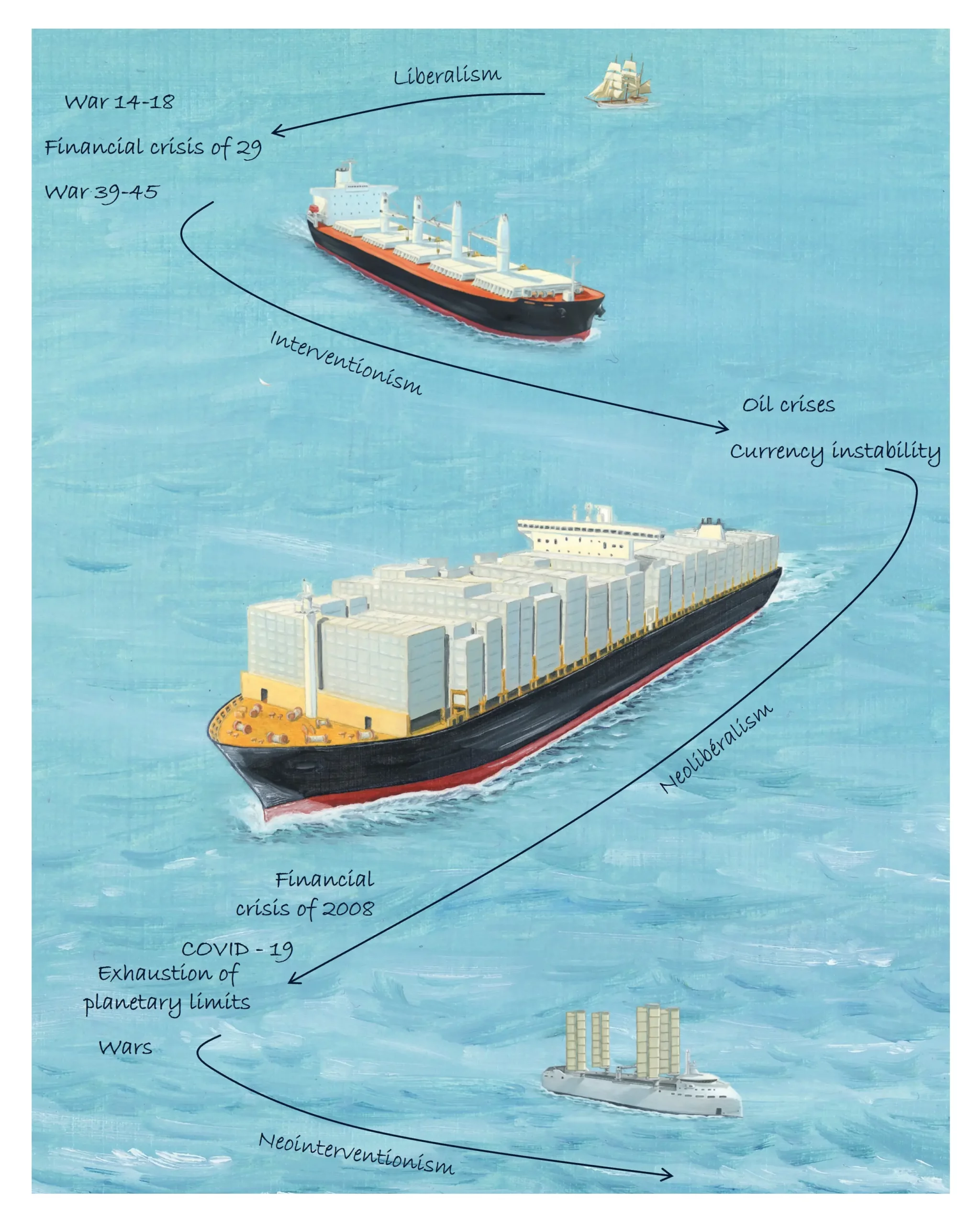

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, liberal ideology prevailed: the State should intervene as little as possible in market forces.

However, the economy was still largely closed and foreign trade was marked by colonialism: sugar, cotton, rice and a few other raw materials were imported from our colonies, while industrial products (refined sugar, soap, metal tools, etc.) were exported.

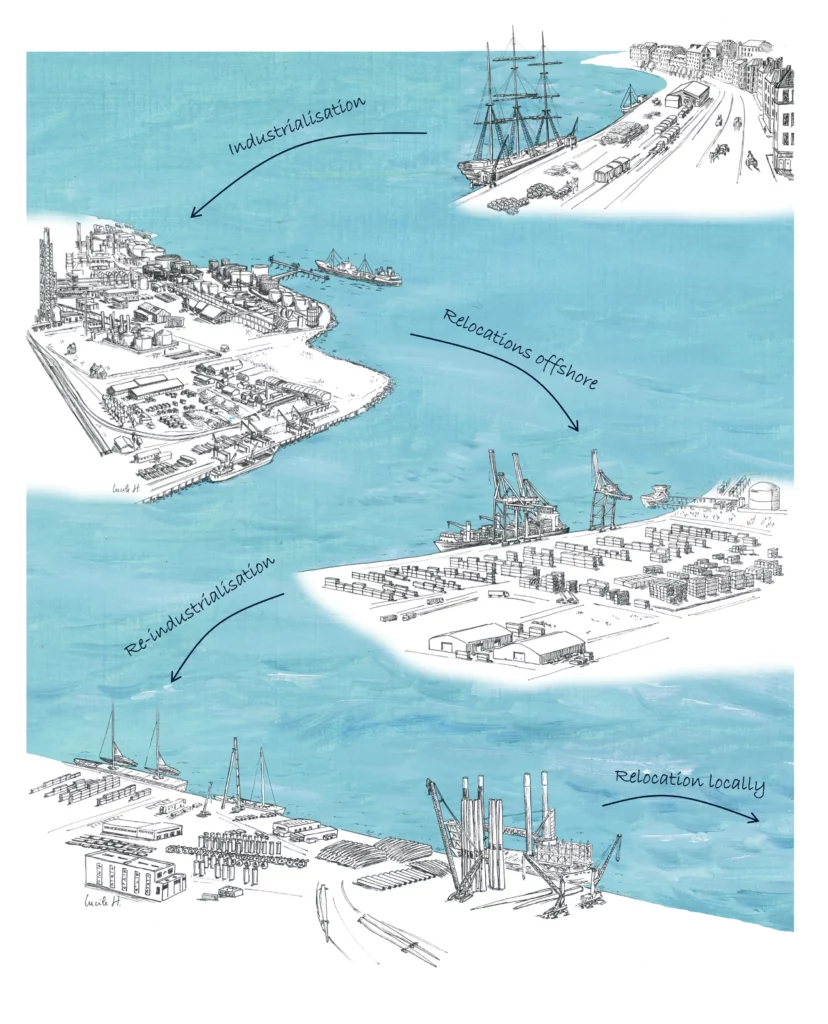

The ports are places for breaking bulk, storage and handling activities, but also for trading, with the presence of exchanges for tropical products. Processing activities are often located nearby, particularly in relation to products from the colonies, although these functions remain secondary.

Ports are at the heart of towns.

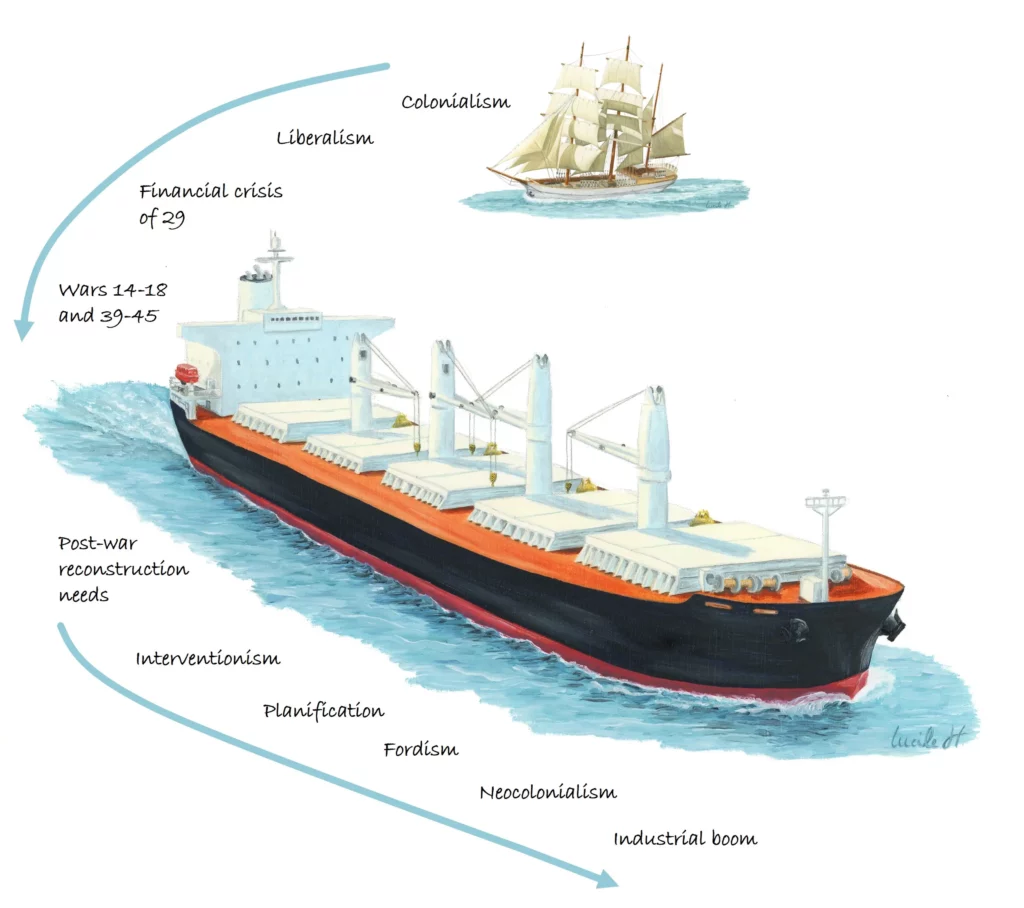

After the financial crisis of 1929, the State regained control of the economy and began to plan. After the two world wars, this role was reinforced by the country’s reconstruction needs.

The economy is still fairly closed and foreign trade is still characterised by the import of raw materials and the export of finished products. There is talk of neo-colonialism.

With technological advances, Fordism revolutionised industry: standardisation of tasks and specialisation of trades meant that production rates could be increased and mass production achieved.

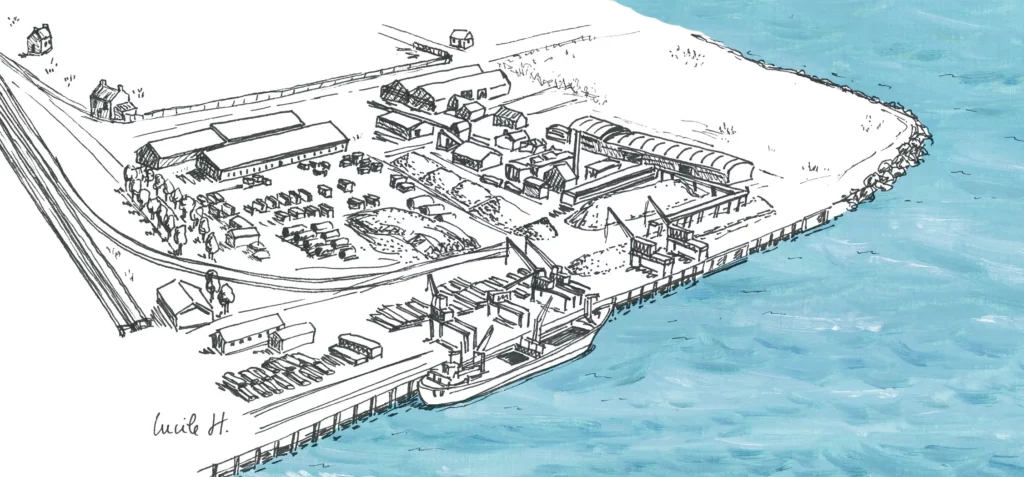

Ports had to cope with a significant increase in imports of the raw materials needed for industry.

Ships are growing and specialising to supply industry more efficiently. Ports are also growing and specialising their quays and platforms.

Ports grow out of cities.

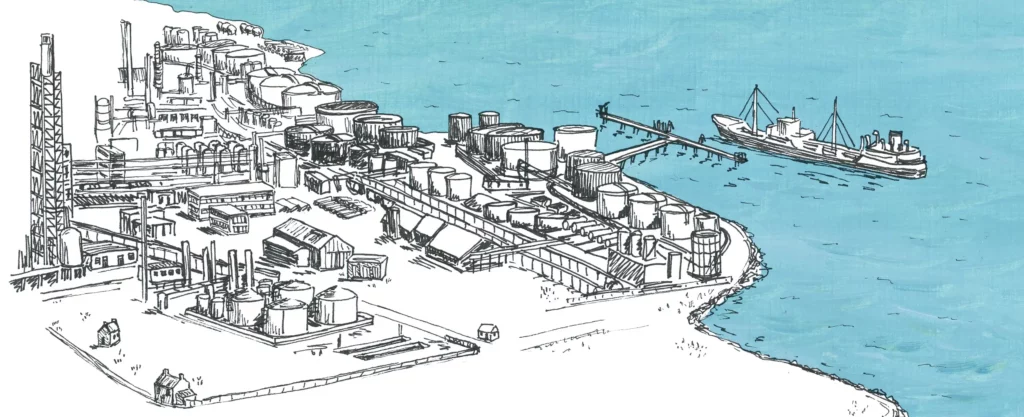

Increasing demand for refined petroleum products eventually raises the question of continuing to import from abroad.

In order to strengthen our sovereignty, the import of crude oil is tax-free, which makes refining on French soil more profitable than importing finished products.

Land are acquired in the ports to set up this new industry. French refineries are built alongside the quayside for greater industrial efficiency. Steel and petrochemical complexes are built alongside them.

The industrial port zone is born. Gradually, other industries move in.

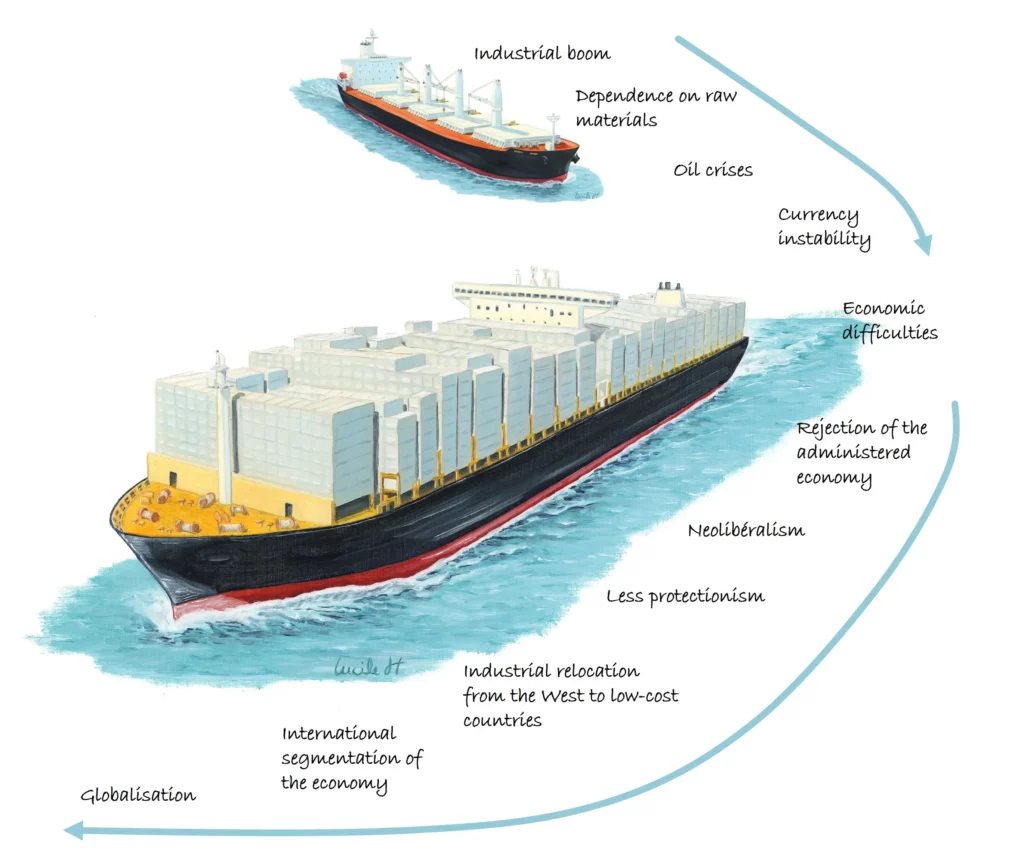

The two oil crises of the 1970s led to inflation and a sharp slowdown in production. This lack of growth (stagflation) led to a rejection of the administered economy.

With the spread of neo-liberal ideology, protectionist measures that isolated national economies from each other were lowered. Globalisation came about: the international segmentation of the economy and the interdependence of economies. In France, this led to relocation and de-industrialisation.

In the ports, it is becoming difficult to fill the ZIPs. The steel industry is facing relocation to low-cost countries. Oil and gas imports were falling.

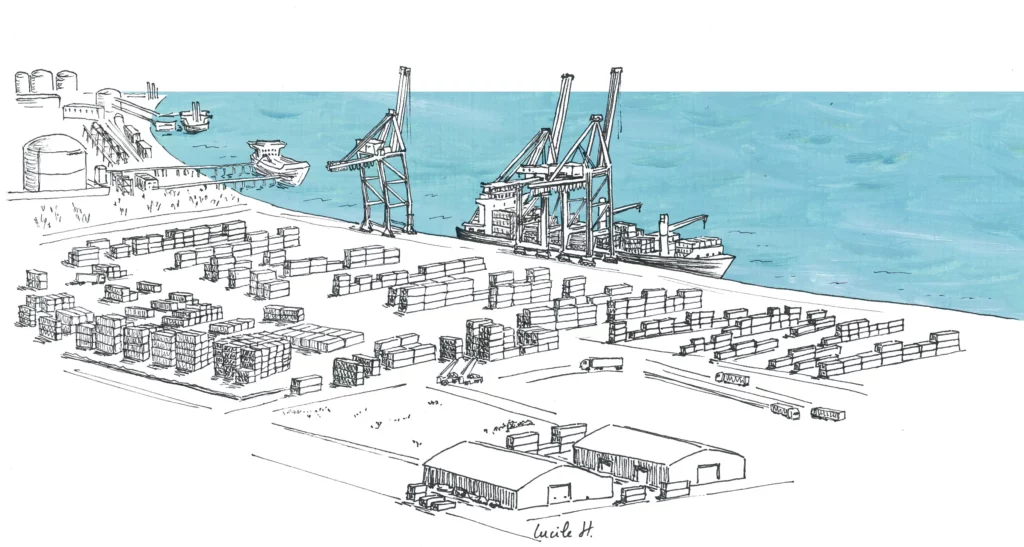

The container, invented in the 1960s, took off with globalisation, which it in turn facilitated through the efficiency it brought to the exchange of goods, particularly manufactured goods (standardisation and economies of scale).

The organisation of container lines requires the port network to be organised into hubs and secondary ports served by feeder lines.

Globalisation and liberalisation of the transport sector are making traffic more volatile, and competition between ports is intensifying.

Ports are developing their logistics activities.

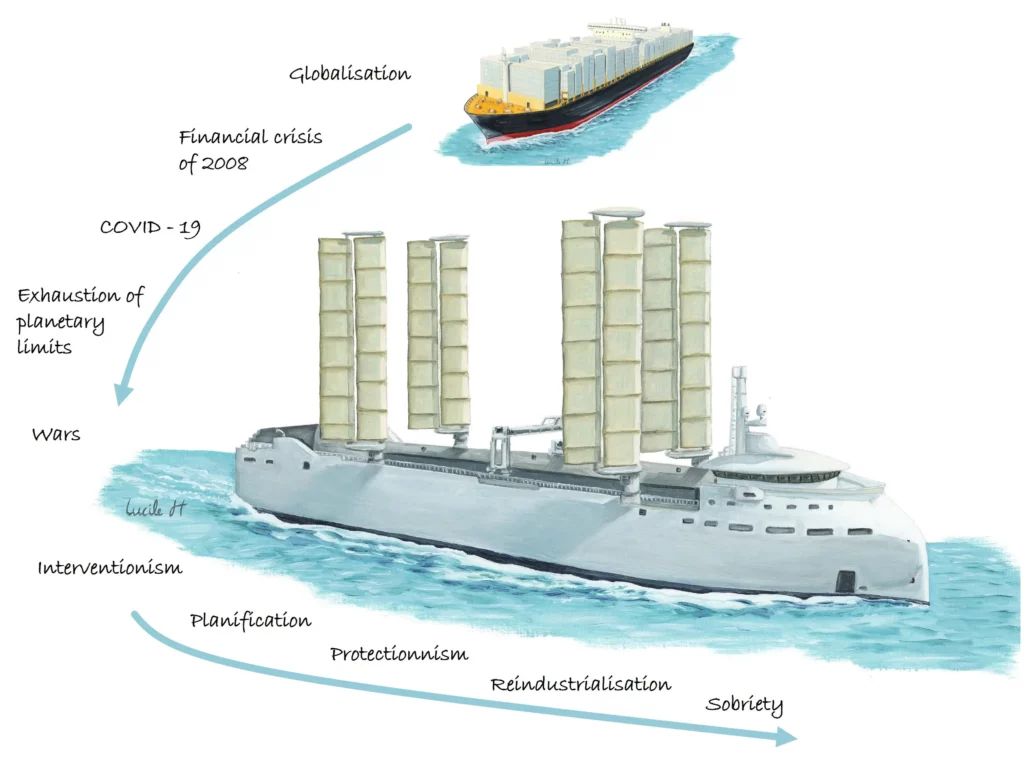

The COVID crisis of 2019 has raised awareness of the planetary limits being reached and the dangers of excessive economic interdependence for the sovereignty of States.

Protectionism and interventionism are making a comeback to relocate strategic economic activities.

Planning is making a comeback to make it possible to move away from fossil fuels and reduce our material footprint: reducing consumption, reindustrialising with new energy vectors (biogas, hydrogen, heat pumps, diesel, etc.), and new sources of electricity production (solar, wind, marine energies, a return to nuclear power, etc.).

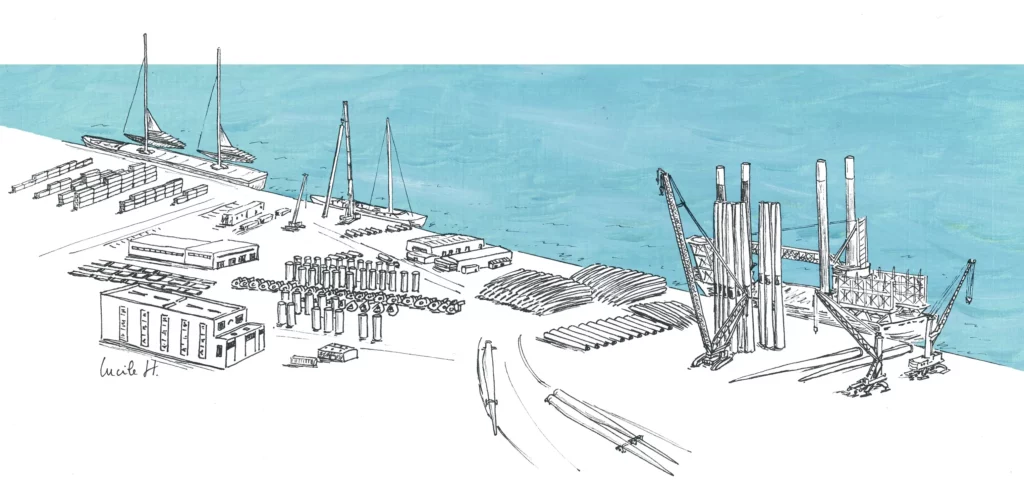

Ports are keeping pace with this re-industrialisation by adapting their infrastructure to accommodate new activities (marine energies, wind propulsed shipbuilding). Port land is once again in demand for fuel production plants and the recycling industry.

Ports are developing economic intelligence and logistics services to reduce the need for transport (relocation of purchases and sales) and the material and CO2 footprint of incompressible transport (shift to mass modes, light and zero-emission vehicles, etc.).

The port is becoming a developer of new, shorter transport lines using smaller means of transport to complement reconfigured long-distance links.

Its business model is diversifying and its integration into the local area is increasing.

See you soon.

Lucile